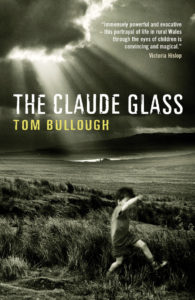

Set in the Welsh Borders in 1980, The Claude Glass charts an unlikely friendship between two neighbours; Robin, the seven-year-old son of English hippie sheep farmers, and Andrew, a child so neglected by his impoverished parents that he is left almost mute, seeking solace among the farm dogs.

Exploring his parents’ semi-derelict farmhouse, Andrew finds an antique convex mirror – a Claude Glass – and, gazing into it, the two boys see their wild, rural landscape strangely ordered. But this comforting vision proves fragile as tensions and sexual jealousy rock the adult world around them.

So says the cover.

To start with feral children. Take a child like Kamala, who grew up with wolves in India in the 1920s, who ran on all fours, who developed preternatural smell and night vision. What did she see and think? What happened in her mind when she was brought to an orphanage, when other children tried to approach her? One thing I learnt when I was writing the story of a kamikaze pilot in A was that it is possible to enter someone else’s mind, feel what they feel, see what they see. In dreams, after all, the parameters of self can move around freely – you can be gay, straight, man, woman – and writing has a lot in common with dreaming. As an exercise, I think the thing to do is to go right back to the beginning. You can understand Kamala if you start from the point at which she was unaltered, when she could have become a normal, socialised being – party, like the rest of us, to what Russell Hoban calls the “limited reality consensus”: the mesh of rules, habits, blindnesses and assumptions that makes human sanity, survival and society possible.

So, in The Claude Glass, Andrew is a kind of feral child. He lives among the sheepdogs on a Welsh hill farm, not among the wolves in a forest in West Bengal. He’s neglected, not forgotten. He’s a boy nearly seven years old, with the capacity to be normal, but his reality is only part-developed; it barely shields him from the wildness beyond the limits of normal human reality, and it is infused heavily with elements of dog.

For me, a book starts with a coming-together of ideas. I lived for much of my childhood on a farm in Radnorshire, but that doesn’t make for a story; it doesn’t even provide a real starting point. A book begins when two ideas harmonise. If you allow them, those ideas will then breed, attract other ideas and create new harmonies and that is when a book starts to take shape. It’s in these harmonies that the stories lie, and Andrew would be no story at all if he wasn’t at once innocent Romantic ideal – a portal to the wildness – and desperate kid of half-mad parents, who suffers abuse, howls in thunderstorms and wants nothing so much as to be normal.

The central harmony of The Claude Glass is the friendship between Andrew and Robin. Robin is the son of idealistic English immigrants – hippies, Romantics – who live on the far side of the hill. As a seven-year-old boy, he is part-wild himself, delicate and imaginative, a lover of wind and rain, but he is being dragged inexorably from this comfortable thoughtlessness into a world of long division and longer bus journeys to the nearest decent school. Naturally enough, he doesn’t want to go. Unlike Andrew, Robin’s path to social adjustment is laid out in front of him. He yearns for the freedom of Andrew’s life and the imagined mysteries of his family’s half-ruined farmhouse (once owned by William Wordsworth’s brother-in-law). For Andrew, it is all the other way round. For him, the past offers only dogs, mud and perpetual rain, whereas Robin and his captivating mother, Tara, are the golden face of the world beyond the farm.

The key thing in writing is belief. You must believe that you can enter someone else’s head, and you must believe that the book will reveal itself, in its own time, in its own way, regardless of any rules you – or anyone else – might previously have laid down. You are there to allow it. When I was first thinking about The Claude Glass, the three things floating around my head were my childhood, a feral child and the distant connection between Radnorshire and the Wordsworth family. Looking for possible themes and scraps of information, I turned to Juliet Barker’s Wordsworth: A Life, and I was reading along merrily when I came to page 281:

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the fashion was for the ‘picturesque’, a word which meant, quite literally, ‘like a picture’… No self-respecting tourist in search of the picturesque travelled without his Claude-glass, a plano-convex mirror of convenient pocket-book size through which he would view the scenes and objects to be admired. It seems wholly appropriate that to do so he had to turn his back on the real living landscape in order to see its image reflected in miniaturized form and neatly contained within the mirror’s frame. In other words, reduced to a picture.

In the whole of the biography, I marked only this single passage (fiercely, in black), although the subject had, at the time, no obvious connection to anything I was writing. I continued my researches – travelled to Grasmere to read Dorothy Wordsworth’s unpublished 1826 Radnorshire journals, spoke to David Bentley-Taylor, author of Wordsworth in the Wye Valley, just before he died – but still this obscure optical device refused to go away. With the Romantics’ preoccupation with seeing the world for itself, unpolluted by preconception, it obviously had some connection with the themes I was thinking about, but I had decided that Andrew should find a Claude glass in the ruins of his family’s farmhouse long before I realised that it reflected his own experiences perfectly. In the context of a “limited reality consensus”, what was Andrew’s story, after all, if not his discovery of a fragile, constrained, but ultimately human means of seeing?

Buy online

Order from Waterstones

Order from Amazon.co.uk

Order from The Hours in Brecon

Video Diary

from the BBC’s Wales Book of the Year website

Extracts

Reviews

“It went straight into my bloodstream and I started dreaming it that very night. Magic!”

Gwyneth Lewis, first National Poet of Wales

“Written with a poet’s sensibility and eye for telling detail, this novel about the difficulties of comprehending otherness has a lyrical intensity. The Claude Glass, discovered by the boys, is a convex mirror that distorts one’s perception of the landscape – a perfect metaphor for this exquisitely written slice of rural ‘dirty realism’. (4/5)”

Mail on Sunday

“This is a novel of compelling complexity of thought and feeling, sustained by the authenticity of its rich detail. A sheep’s agony in labour, a moribund tractor – Bullough endows the components of his scene with a poet’s sense of their quiddity and a novelist’s appreciation of their human significance.”

Independent

“This often unnerving tale of romanticism suffocating beneath the weight of flinty pragmatism shows Bullough to be a very gifted writer indeed. In Andrew, he’s created a truly memorable fictional character, but a word of warning: books rarely end as heartbreakingly as this one. (5/5)”

Independent on Sunday

“An intense and accomplished novel”

Independent on Sunday, The Top Fifty

“Incredible… I thought ‘The Claude Glass’ was an unusual and incredibly accomplished piece of writing, silently impressive and one that rewards you in many ways”

Savidge Reads

“A great read.”

Sunday Tribune

“Immensely powerful and evocative – this portrayal of life in rural Wales through the eyes of children is convincing and magical.”

Victoria Hislop

“The Claude Glass delivers just what the title promises – a beautifully delineated miniature of a family struggling with the reality of the rural dream.”

Francine Stock

Show more reviews

“A superb book from the border, bright with its light and dark as its weather. It is full of truth, romantic and real, as vivid and suggestive as the world seen through a child’s eye. The Claude Glass feels like the beginning of something serious and remarkable: an honourable successor to Chatwin’s On the Black Hill, springing from the same ground.”

Horatio Clare, author of Running For The Hills

“The Claude Glass… is the account of the relationship between two small boys in the Radnorshire mountains. The still young author beautifully suggests the cultural heritage and encumbrances of each while setting them against an intimately evoked landscape and a subtly complex rural community.”

Paul Binding, Books of the Year, Independent on Sunday

“It’s a bold move for anyone to write pastorals in an age of the urban novel. And Tom Bullough seems quite clear, in this consummately well-written book, how dangerous rural enchantment can be.”

The Times

“The book’s a triumph, ‘on the dangerous edge of things’, as Greene put it… amazingly good”

Paul Ferris, author of Dylan Thomas: The Life

“Beautiful! Poignant! Dazzling!”

Chris Stewart, author of Driving Over Lemons

“Half fairy tale, half poem, Tom Bullough’s dreamlike novel remains with you long after the final sentence.”

Kitty Aldridge, author of Pop

“a difficult but beautiful novel”

Susan Hill

“the lovely novel The Claude Glass”

Erica Wagner, The Times

Hide additional reviews